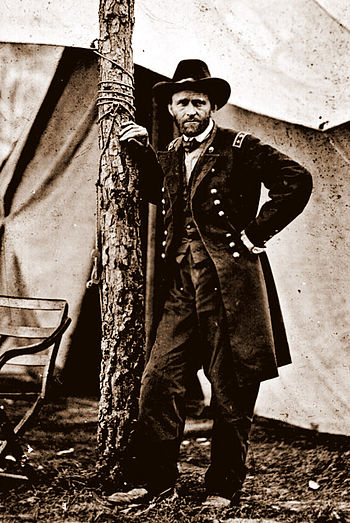

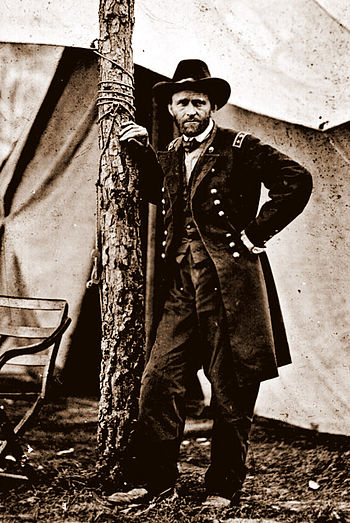

English: Gen. U.S. Grant – Category:Images of people of the American Civil War (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Today we’ll examine our first President through the lens of the Value Zodiac. He rode a roller coaster of failure and hardship mixed with almost unimaginable glory and achievement. He rose from obscurity, personal struggle, and a history of painful personal setbacks to lead great armies in pivotal battles and later a great nation only to lose everything and get filing used his last days to seek ultimate victory over time itself.

I’ve been studying the history of the American Civil War since I was in elementary school. I remember being riveted to the television to watch the 15 hour long Ken Burns documentary on the subject. (Impressive for a 13-year-old).

One of the most compelling personal stories was that of the remarkable journey of Ulysses S. Grant. Today, we will look at general and later President Grant through the context of the Value Zodiac. The evidence strongly supports the idea that Grant most closely identified with the Farmer archetype. The following paragraphs explore Grant’s history to illustrate why the Farmer archetype figures so prominently in his life’s journey.

Grant grew up a quiet boy in Ohio. His father, Jesse, was a tanner and very successful businessman and Galena, Illinois. But Grant identified more with his mother who was uncommonly introverted. Grant was quiet-mannered but developed a knack for animal husbandry, particularly horses. He was a fantastic horseman. Jesse Grant believed his son to be ill-suited for a business career and got him an appointment to the military academy at West Point. His performance at West Point was unremarkable. He graduated in the middle of his class. He did well in mathematics and geology which were well-suited to his introverted temperament. He was initially deployed to Missouri where he met the love of his life, Julia Dent. The two would later marry after a secret four-year engagement. (Julia’s father disapproved of Grant’s prospects through a military career.)

Despite having large reservations about the cause, Grant followed Major General Winfield Scott and future President Zachary Taylor to Mexico. Grant thought the Mexican War was a tremendous mistake. Years later, he said, “I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day, regard the war, which resulted as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger nation against a weaker nation.” Grant, upon later reflection, came to see the American Civil War as a form of divine punishment to atone for the sin of the Mexican war. Grant believed that nations, like individuals, are punished for their transgressions. Here we see the values of the Farmer archetype represented. The concept of karma — the belief that you reap what you sow — is well represented in his thinking.

Despite his reservations about the war, Grant nevertheless resolved to do his job. He was a soldier and did not feel it was his place to cast judgments on people who wrestle with difficult decisions such as putting men into jeopardy on the battlefield. But he used his time in war to educate himself. He learned about military leadership by carefully observing the actions and decisions of his commanders. The two main leaders of the Mexican War on the American side were Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Grant identified much more with Taylor, who was indifferent to parade-ground pomp and circumstance or formal military protocol. By contrast, Winfield Scott reveled in the ceremony. After winning the Battle of Chapultepec, Scott celebrated lavishly, which Grant thought was quite distasteful.

After the war, Grant never demonstrated any high sense of ambition. He wish to simply fulfill his service commitment and move back into a more quiet civilian life. Grant was soon deployed to the west. He was unable to pay for passage for his wife and children. Missing them greatly, Grant tried a number of ways to raise additional money to bring his family to him. He tried and failed at several different business ventures. On one occasion, one of his partners succeeded in swindling him out of his investment. Grant’s distance from his family, aggravated by his record of financial folly and boredom from peacetime army life, drove Grant to abuse alcohol. It is speculated, that this alcohol abuse was the reason for his sudden resignation for the Army in the 1850s.

Grant left the Army and decided to try his hand at farming. His father had offered to bring him on in his Galena, Illinois tannery business but only on the condition that Julia and his kids live with relatives in Kentucky because money was so tight. The Grants, after being separated by years during his deployment, refused to be parted again. As so often happened in Grant’s life, while he had the skills and temperament to be a successful war fighter, he demonstrated little talent for doing anything else. He had no aptitude for farming. His crops failed. Grant turned to bill collecting, but didn’t have it within him to press for payment. He tried selling insurance, but was terrible at sales. Grant ultimately ended up in his father’s tannery after all, after Jesse Grant again offered him a job — this time without condition.

Grant’s early life gives us clues to his character. Introverted and bookish and despite his skill as a horseman, he never demonstrated a strong ambition for promotion. He was immensely devoted to his family and it pained him when they were parted. Grant himself, was a man of principle, but refused to let his personal preferences get in the way of doing his job. He demonstrated a certain level of social naivety and incompetence by being swindled by people close to him and being indiscreet with his personal struggles. By the late 1850s, all evidence pointed toward Grant being relegated to obscurity — not the least bit noteworthy. Grant recognized this and was content with it.

When war broke out, he was tapped to muster volunteers in Illinois. However, Grant remembered that he actually performed quite well during the Mexican War. He recalled that of all of the things he tried to do, war fighting was the one area, apart from his successful family life, where he felt he was competent and talented. He wanted the field command. When he got his chance, he soon became recognized for his command ability — winning battles at a time when Union victories were few and far between. He took command and never looked back.

Grant had several traits that made him an exceptional military leader. He conceptualized and operationalized textbook military campaigns. His training in the quartermaster’s corps in the Mexican War impressed upon Grant reinforced the importance of keeping an army well supplied, well fed, and ready to fight. Grant was a master at military logistics. Grant had a simple approach to war-fighting. He developed a strategy and refused to be distracted or diverted from executing that strategy. While other commanders were prone to question their strategy in response to enemy movements or actions, Grant continued to press on with complete faith that it would work out (also echoing the Farmer).

A quote by William Tecumseh Sherman does a great job illustrating this concept.

“I am a damned sight smarter man than Grant. I know more about military history, strategy, and grand tactics than he does. I know more about supply, administration, and everything else than he does. I’ll tell you where he beats me though and where he beats the world. He doesn’t give a damn about what the enemy does out of his sight, but it scares me like hell. … I am more nervous than he is. I am more likely to change my orders or to countermarch my command than he is. He uses such information as he has according to his best judgment; he issues his orders and does his level best to carry them out without much reference to what is going on about him and, so far, experience seems to have fully justified him. “

Comments to James H. Wilson (22 October 1864)

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant standing by a tree in front of a tent, Cold Harbor, Va., June 1864. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In addition, Grant never got bogged down in military command politics. Unlike other generals who flamboyantly assumed command of the Army of the Potomac, Grant felt no need to replace Gordon Meade (who had acquitted himself well at the battle of Gettysburg the year before). Grant’s lack of pretentiousness endeared him to his men. He was often seen along roadsides where his army marched. He wore a simple dust covered private’s jacket with general stars. He was a soldier’s soldier, much like US General Omar Bradley would be almost 80 years later in World War II.

But Grant’s greatest gift was being remarkably unflappable and coolheaded under fire. There are a few people who experience a rush of adrenaline instead of fear during battle. Grant was one of those people. Battle energized him and increased his focus. He did not react impulsively to bad news. He was quick to improvise and to exploit opportunities. Grant always was a soldier doing a soldier’s job and doing it in a masterful way.

At the conclusion of the war, Grant shared Lincoln’s sense of magnanimity. He felt no desire to punish his former enemies. He acknowledged how the Confederates fought for closely held values and beliefs. He understood that people fighting for what they believe in deserve respect, even if they didn’t agree with their aims. This kind of humble and respectful demeanor that he brought to negotiations was key to begin the healing process for the country.

Grant always honored the chain of command. It was only when he climbed the rungs of that military hierarchy and later civilian leadership, that he came into his own. He had earned the right to advocate for his principles, unlike years before when he objected to the Mexican war. As President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant was the only President who actually cared about promoting civil rights until Lyndon Johnson took up the issue a century later. He brokered peace agreements between warring factions both in the United States and abroad. In many ways, his post-military life is echoed by another farmer in American history, a peanut farmer from the State of Georgia — a good man of great principle, who was poorly equipped to deal with the subtle intrigue of American politics — President Jimmy Carter.

Though Grant was never unpopular, his troubled and corrupt Presidential administration did impact his popularity. But like Jimmy Carter, post-presidency, Grant enjoyed resurgence in popularity through his effective peacemaking ability. As is characteristic of the Farmers, like Grant, they make excellent peacemakers because although they do have strong personal principles, they are so dogmatic about them to make it difficult to understand or demonstrate respect for the principles of others.

As the war ended, Grant had developed a keen sense of evaluating the motives and character of others in his presence. This insight served him well as President Lincoln’s elected successor. Andrew Johnson, the Vice President who assumed the presidency upon Lincoln’s death, became more and more vulnerable and Johnson made several attempts to eliminate Grant as a potential rival. Grant had learned to see these threats for what they were and was able to avoid getting ensnared by them. Grants weakness, however, was that he never learned how to see threats that were hidden. The quote from Sherman above is particularly poignant. Although not caring about the actions of an enemy “out of your sight” often serves you well in a time of war, such a disposition is deadly when it comes to politics. Since Grant always took on challenges head-on, he naïvely assumed that others would do so too. This made his dealings with others extremely costly. He was blind to the rampant corruption of his Presidential administration. His lack of awareness also made him an easy mark. His business associates swindled him on multiple occasions. The last time this happened, well after his retirement from public life, left his family destitute. He simply had no awareness for threats he couldn’t see and it cost him dearly.

Ruined by the failure of one of his partnerships through no fault of his own, other than trusting the wrong people, Grant faced the prospect of his family living in poverty. To make matters worse, Grant was diagnosed with throat cancer. Determined to provide for his family and to pay off his debts, Grant set to work on completing his military memoir. He wrote day after day sometimes thousands of words each day. Each day he became weaker and weaker. By the end he was no longer able to eat or speak. He finished his work just four days before he passed away — restoring his family fortune and honoring all of his debts.

Grant’s memoir is considered one of the best autobiographies by a world leader in history. His tone was simple, clear, and without self adulation or pretense. The work is also noteworthy in how it teams with an extremely positive and optimistic perspective — the optimism that is so associated with the Farmer archetype. The last chapter of his memoirs, Conclusion, is essentially a list of the goodness of people throughout the world and expresses Grant’s hope for a better world — a world that can shed some of the animosity from its wars throughout history. He also discusses his confidence in a new America, strengthened by the Civil War and able to stand proudly among the community of nations. He also expresses his belief that the American people will achieve a new level of peace.

He wrote: “I feel that we are on the eve of a new era, when there is to be great harmony between the Federal and Confederate. I cannot stay to be a living witness to the correctness of this prophecy; but I feel it within me that is to be so. This universally kind feeling expressed for me at a time when it was supposed that each day would prove my last, seemed to me the beginning of the answer to ‘let us have peace’.”

Grant is remembered for his excellence as a military commander. But I think his greatness is really tied to his understanding of the life of the common person and the common soldier that was made possible by his humility and his utter lack of pretense. He was always guided by strong individual principles and values. He was a loving husband and father. Grant is a unique American story. And although he was a terrible farmer, he is one of the best embodiments of the Farmer archetype in American history.

Grant is remembered for his excellence as a military commander. But I think his greatness is really tied to his understanding of the life of the common person and the common soldier that was made possible by his humility and his utter lack of pretense. He was always guided by strong individual principles and values. He was a loving husband and father. Grant is a unique American story. And although he was a terrible farmer, he is one of the best embodiments of the Farmer archetype in American history.

-

- English: Ulysses S. Grant seated on porch with his wife, Julia, and son, Jesse. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

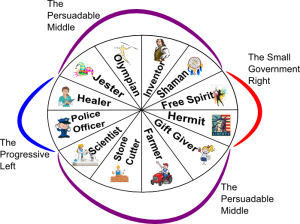

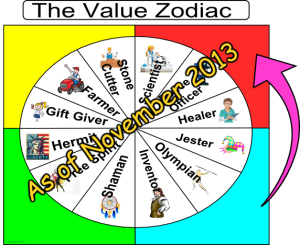

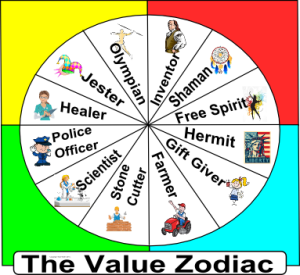

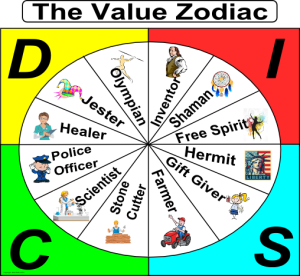

The Value Zodiac is a conceptual model that is used to measure an individual’s worldview. It is a powerful tool to explain human motivation and behavior, which can be used for such important purposes as conflict management, effective persuasion, analyzing ethical dilemmas, etc.